My grandfather sat down with me over winter break my first year in graduate school. “Amy Love,” he said, “I want to tell you our weekly schedule. On Monday we wind the clocks, Tuesdays the gal comes to clean the house, on Wednesdays we go get Grandma’s hair done and have Chick-Fil-A for lunch . . .” I had no idea why he was sharing this information with me; nevertheless I listened carefully and stored it away somewhere in my mind. Within four months, he would be dead, and my grandmother would be left in the care of my mom and her brother. My grandfather had entrusted me with a piece of their story, so that I could keep things consistent for Grandma. Because what he sensed but perhaps had not fully admitted to himself – what none of the rest of our family members had any idea was occurring – was that my grandmother was rapidly losing the details of daily living.

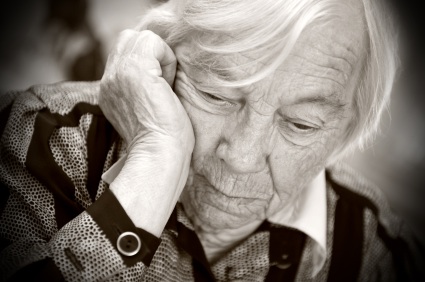

Her journey with Alzheimer’s followed the path that many dementia patients experience. What her husband witnessed was her loss of short-term memory and her ability to readily locate herself within a specific time and place. By telling me about their weekly schedule, my grandfather was trying to ensure that her memory loss was mitigated and that her routines were kept secure for her. In the eight years that followed his death, my grandmother lost not only capacity to maintain her daily appointments; her brain lost the ability to recall family member’s faces, her own name, how to swallow, and eventually how to fight the infection that would cause her death.

And, all along the way, she lost stories.

When I was a young girl, I used to delight in my grandmother’s tales. Sitting at the kitchen table as my grandfather did the dinner dishes, I would prompt her, “Tell me about the time Mom . . .” or “What was it like in England when you were growing up?” During the early years of her dementia, those stories continued to be shared, even as she consistently forgot whether she had eaten breakfast or what was on the agenda for the next day. Indeed, it often felt as though she were living in the times and places of the narratives of her earlier life.

New stories appeared too in her early stages of Alzheimer’s – stories I never had heard before, stories that my exceedingly polite grandmother never would have shared if the strong filters of decorum had not been obliterated by the plaque building in her neuronal pathways.

What happens to our stories when dementia makes them inaccessible to us?

One of the most challenging aspects of caring for dementia patients is the loss of their narratives. Family members feel hurt as the person they love no longer remembers significant events they shared and eventually looks at them without any recognition at all.

It can be frightening to acknowledge that someone we love lives in a different reality than ours. During the first few years of my grandmother’s disease, much of the conventional wisdom guided caregivers to keep focusing patients on “reality”, to continue to inform them of the circumstances in which they actually existed and negate those they said they were experiencing.

That felt cruel to me, so I never adopted those practices. This woman was amongst the first people to hold me and tell me stories; she listened to my little girl tales, she wrote her autobiography as a pre-teen, and she was the keeper of so many family narratives. Her stories were very present and real to her, and she had no need to be forced into someone else’s reality.

And she still had so many stories to share. These precious gems would have disappeared if I continually reminded her that she was an elderly woman this hot Alabama afternoon in 1993 and not a girl buying fish and chips wrapped in newspaper from the corner shop on a rainy day. These stories could only be accessed if I entered into her reality rather than futilely attempted to force her into mine.

Thankfully, knowledge about dementia and guidance regarding its care have both changed greatly in the intervening years. We now recognize the importance of meeting patients where they are, particularly when that “where” may be hundreds of miles away and decades ago.

Some of the most fundamental reasons humans construct narratives are to:

Some of the most fundamental reasons humans construct narratives are to:

- Create order from chaos

- Understand events and people

- Ensure that we may someday be remembered

- Connect with one another

- Be witnessed in our joy and pain, our triumphs and challenges

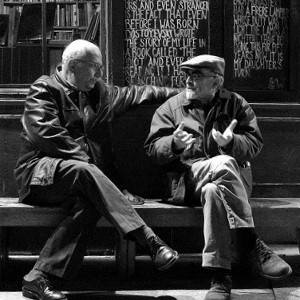

But in a dementia patient, those needs are no longer readily fulfilled, nor are some of them really felt. Grandma quickly lost her mental capacity to create order out of chaos and to understand events and people. She eventually could not grasp her own identity and a need to have it remembered or not. But those other two desires driving human story-telling – to connect with others and to be witnessed – never seemed to disappear, even as her capacity to have them met slipped away from her. It seems to me that when we enter into the stories of those who may have “lost their stories”, we are engaging in the single most significant aspect of sharing narratives – that of allowing these tales to connect us with one another. The content of the story is not what is significant; the sharing is.

Mallory Everhart, a friend and colleague of The Way of Conscious Death, learned to use her experiences in Improvisational Comedy to help her to meet her nursing home and hospice patients where they are, to enter into their world as a way of connecting with them and witnessing them. As with comedy and playing with young children and even watching a movie, when we allow ourselves to enter the portals presented through connecting with dementia patients, we are given access to new worlds. This is a profound gift. The depth of connection presented to us far surpasses time and location and even words. To tap into this possibility, listen to Mallory’s inspired poem “Language Lessons”:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LcY4MrTcSr0

Can you change your language in order to connect with a loved one who no longer recognizes you?

Can you give and receive the “I love you” present beyond the particular “I” and “you” that no longer mean anything to that beloved?

During the middle years of Grandma’s illness, long after she had lost her schedule-keeping powers but before she lost spoken language altogether, I noticed a pattern to her story-telling. The age of whomever she was speaking with always seemed to guide her narratives. When I was there, she talked to me as though she were a very young woman; we chatted about dating and wondered what our futures would bring. With my mother, however, she also became a mother of young adults and discussed her children as though it were decades before. I marveled at this pattern for years and eventually recognized that she was, likely without any consciousness, entering into my world each time I was with her. Without any training or intent, she was weaving together her reality with mine.

Through each of those interactions, she taught me how to do that very same thing, how to allow whomever I am with to guide me through the portal and into their world. Since then, I have worked with so many patients whose memory fades but whose stories do not.

One hospice patient, Rosella, who had vascular dementia, never was able to track the names of her various caregivers. But she never lost her capacity to connect with the essence of each of us. Each week, when I entered her room and announced, “Hi Rosella. It’s Amy. I’m here to visit with you,” she would look up at me and ask, “Who are you?”

“I’m Amy.” Slowly she would nod her head, as if in recognition.

Then she would say, “Oh, I love you.”

Eventually, she did not even wait for my reply before offering her answer; so that the statement followed right upon the question – “Who are you? I love you.”

Her love was not dependent on her remembrance of my identity; it was not dependent on my identity at all. The story of her love transcended both of our realities.

That story continues long after she died. And it will continue long after I die.

As with all true stories, its offerings are both timeless and endless.

2 comments to “Losing Stories: Ways Dementia Affects Our Narratives”

You can leave a reply or Trackback this post.

Christine Connor - January 20, 2018 at 1:04 am

Beautifully written… touched my heart. I loved Amy’s grandparents, both of them, after reading this. I have not traveled this road with a loved one so her article presented more insight into this harsh reality

Amy Agape - January 20, 2018 at 6:07 am

Thanks for reading, Chris! It is indeed a harsh reality; and it is an opportunity for ever more love.