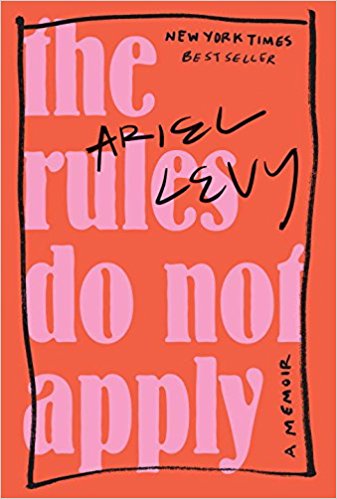

Ariel Levy’s The Rules Do Not Apply: A Memoir is a raw, intimate account of the grief the author experienced during one unfathomable period. In a few short weeks, she lost her child, her spouse, and her home.

Ariel Levy’s The Rules Do Not Apply: A Memoir is a raw, intimate account of the grief the author experienced during one unfathomable period. In a few short weeks, she lost her child, her spouse, and her home.

Perhaps what Levy’s volume most clearly communicates is that if we live long enough, we will each experience loss – and sometimes we will lose almost everything we hold dear in one huge swath of destruction. To surrender to that loss is radical in a culture that tells us (as it repeatedly instructed Levy) that we do not have to lose anything, that we can continue to gather and accumulate relationships, possessions, pieces of identity.

Masterfully weaving together memories of childhood and adolescence, details of family members and friends, with her narrative of those weeks of death and the following months of grieving, Levy leads us through her landscape of loss. Many of us find that our periods of great grief take us forward and back in time; our memories float together, and we try (but usually fail) to gather them together into one clear story that makes sense.

An exceedingly accomplished journalist, Levy approaches her own story just as she would an article for The New Yorker, where she has worked for years; she gathers facts, she searches for evidence, she struggles to create order out of chaos. The instrument she wields to dissect her life after it has fallen apart resembles at times a surgeon’s scalpel and at times a lumberjack’s axe. This, too, may feel familiar to those who have experienced grief, which Levy adeptly describes:

Grief is a world you walk through skinned, unshelled. A person would speak to me unkindly – or even ungently – on the street or in an elevator and I would feel myself ripping apart, the membrane of normalcy I’d pulled on to leave the house coming undone.

Thankfully, Levy eventually abandons the project of understanding her losses and embraces the work of experiencing them instead. Learning to accept the past rather than deconstruct it is something that greatly helps in our grieving, in my experience. Whenever I spend time trying to understand what happened or argue with circumstances, I find that I have moved out of my heart and into my head; it’s a way I have of avoiding grief, actually. I may be thinking about my loss, but I am doing that in a way that circumvents me actually experiencing it. And this is never healing.

The loss that underlies all the great losses in this horrendous period of Levy’s life is the loss of her naïveté, her view of the world as something to be constructed, manipulated, taken by storm. This reveals perhaps the one consistency that crosses all boundaries of unique losses – that whenever we grieve the end of something, be it a relationship, job, home, or loved one, we are in part grieving the loss of a piece of us. We can never again be the person we were before that event occurred. We cannot unlearn the things we learned through the process of losing.

I value Levy’s honesty, her vulnerability, and her transparency. It is very challenging to allow grief to take us into the depths of self-examination, yet she does that and shares the journey with all of us. To me, that is one of the greatest gifts we can give one another – to consciously walk through the wild landscape of grief and loss and to open that landscape up for others to witness. We may not ever encounter the particular triumvirate of deaths that Levy faced during those few short weeks. But we will each face deaths of our own. Hopefully, we will likewise walk into that wild landscape with our eyes and hearts open.