You can watch Being Mortal here

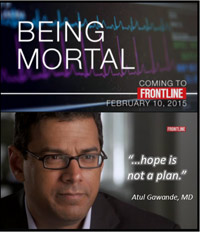

Atul Gawande’s film Being Mortal (Frontline, PBS) examines the limitations of contemporary Western medicine, specifically the lack of training and comfort most physicians have with the most challenging discussions they must have – the discussions about end of life, about prognoses, about how to die.

Atul Gawande’s film Being Mortal (Frontline, PBS) examines the limitations of contemporary Western medicine, specifically the lack of training and comfort most physicians have with the most challenging discussions they must have – the discussions about end of life, about prognoses, about how to die.

As with his book of the same title, this documentary highlights the paucity of education most doctors receive regarding this essential component of patient care. Gawande, a successful surgeon, researcher, and writer, courageously admits his lack of experience in this arena. And the camera follows him as he attempts to rectify that.

Shadowing his colleagues in oncology and palliative care, he takes us along to repeatedly witness these kinds of conversations. We watch as some individuals accept news that they are out of treatment options, while others seem to push away the reality that they are hearing.

The film, written by Gawande and Thomas Jennings, does not make death pretty or easy. It does not create an image of physician as God. That is good, because we have seen far too many of those constructions – of easy, peaceful deaths and of God-like physicians. Death is not easy, and doctors are merely humans who work hard and who do make mistakes.

Anyone who has lived with chronic illness (or anyone who has supported a loved one through this process) has likely come into contact with a vast spectrum of competency on the part of health care professionals, particularly in terms of these challenging conversations.

Years ago, when my doctors were struggling to diagnose my condition, they sent a lung sample to a research physician renowned for her skills in this area. Her reply letter had some good news and some awful news. What struck me as I read it, though, was that she kept referring to me as a “case”. Not once did she use my name or even a word like “patient.” I was only a case. I understood that that was likely the way she thought of all those whose teeny, tiny body parts were shipped to her laboratory to be explored under a microscope.

That makes sense, sort of.

What I have never been able to accept is that there are physicians who also think of me merely as a “case”. They may not use that word, but by their behavior it is perfectly clear that they are not grasping that I am actually a human being who is still living right in front of them. I have been talked about rather than to many times, as doctors consult with one another feet from my bed. I have lain in a cold CT scan machine as the technician looked at my images, gasped, and said, “Man, that is BAD!” One surgeon felt he needed to make a procedure work even though it was apparent that was not possible, so he kept me in that procedure for five hours, pushing and prodding, until I eventually went further into heart and kidney failure.

In none of those instances have I felt like anything other than an interesting case, something to be transfixed by, something to fix.

Fortunately, out of my seventeen years of medical care for this condition, those instances are very, very few.

I have also had doctors who sit with me, repeatedly explaining very complicated heart anatomy and blood chemistry. I have had nurses who spend hours laughing with me about their children and mine. One of my doctors early on had tears in his eyes when he told me about my diagnosis.

During those connections with health care practitioners, I feel like a human being rather than a science experiment.

This is what Gawande’s work begins to address: how do we support people who are dying in a way that honors what is significant to them?

Most important is to be honest – with ourselves as well as with them. Gawande found that a vast number of doctors stressed more what they thought their patients wanted to hear than what they actually knew to be true. Even with his father, also a surgeon, there was this discrepancy. Potentially weeks away from being paralyzed by his cancer, the elderly man was told by his oncologist, “You could be playing tennis by the end of the summer.” Such lies stem from our cultural belief that people want to believe in something that will bring them hope.

But what Gawande learned, what many of us living with chronic and terminal illness already know, is that hope does not need to be found in the longevity of life. We hope for all sorts of things that have nothing to do with how long we live; we hope to feel the sun on our skin one more time, to hold a loved one’s hand, to have the time and energy to say what needs to be said before we die.

This thoughtful film helps redirect our attention back to those hopes, to the priorities that really matter to dying persons.