What Will You Value When You are Dying?

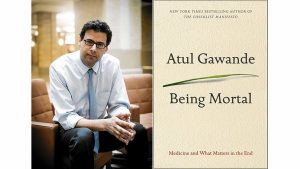

Atul Gawande’s Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End (original publication: Metropolitan Books/Henry Holt & Company, 2014) masterfully integrates many of today’s significant conversations around death and dying, paying particular attention to the need for greater education and awareness regarding end of life needs within the medical system.

Gawande’s training makes him ideally suited to treat this topic. An American surgeon and public health care researcher with both a Medical Degree and a Masters Degree in Public Health, he works in the operating room, the laboratory, and venues around the world where issues of the most pressing local and global health concerns are debated.

And one of those pressing issues – the one closest to my heart – is how we approach the dying process in contemporary Western culture.

Even with all his training and job experience, Gawande shares that he never was taught much about mortality. In medical school, instructions with his first corpse all centered on human anatomy, not on the fact that this corpse had belonged to a human and any implications that created. His textbooks did not contain much discussion about the processes of aging or dying; specifically there was no information about people who are aging and dying and what their experience is.

He was trained how to save lives, not how to care for those whose lives could not be saved.

Gawande’s greatest encounter with death may not have come through his education or his medical practice. Rather, it was the cancer journey of his beloved father, also a surgeon, that seems to have provided him with a lens through which to examine our treatment of those who are dying and our medical approach to prolonging life.

So, like most of us, he became more fully aware of the experiences encountered by those who are dying through a personal connection. If you or someone you love has been given a terminal diagnosis, you likely also have become a student of death and dying in our culture. You have your own stories about our medical system

and its treatment of the dying process.

Being Mortal is a rich tapestry woven together from research of contemporary end of life care in the Western world, stories from Gawande’s clinical practice, and his journey with his father’s death. Gawande critically examines our culture’s approach to death and dying, specifically that of our medical institutions. He visits nursing homes, both those that are rather unremarkable in their care of the patients they serve and those that have reformed entirely how such patients live during their final days, weeks, and months. He engages in the challenging discussions that many of his colleagues may avoid, sharing truthfully with his patients their prognoses.

And he determines that:

In the past few decades, medical science has rendered obsolete centuries of experience, tradition, and language about our mortality and created a new difficulty for mankind: how to die (Gawande, 2014, p. 243).

Is this true? Have we as a culture lost our knowledge of how to die? Is it more challenging to die today than it was centuries ago?

The first time I encountered my own dying, I kept repeating this phrase in my head: “I don’t know how to do this.” After decades studying death on a cultural level and working with dying in spiritual realms, I was ill equipped to die. I had no tools to aid this process and few confidants who would even discuss it with me. I have spent the seventeen years since then attempting to change that – for myself and for others.

Atul Gawande’s Being Mortal has become one of my foundational pieces of support in this quest to determine how to do this dying. His conclusions about What Matters in the End align with my experience. He finds that, although the healthcare industry may focus on prolonging lives, this is not necessarily a priority for those who are dying. This has been true for me. What matters to

me in the end is living fully while I am still here, and that living fully has looked slightly different for me during each of my three meetings with death. While my physicians have been focused on keeping me alive, I have been concentrating on living my life according to what matters to me – regardless of how long that life will last.

The job of a physician, Gawande shows, is to support wellbeing. And well-being really has nothing to do with longevity of life or with prolonging a situation. Well-being all centers around living rather than simply being alive; and the way that this living is done is specifically formed by the reasons one wants to live. These reasons are unique to each individual and need to be addressed by those providing their medical care. These reasons are not just significant at the end of life but throughout our life.

Gawande created a short series of qu

estions we can ask ourselves and those we serve, questions that help us determine what matters to US at the end of our lives. I use these questions frequently – not just when I am in the hospital surrounded by discussions of the drastic measures needed to prolong my life, but also when I am at home and seemingly healthy.

What about you? What matters to you – and what will matter to you as you face your own death? Being Mortal can help you answer those questions.