“This thing I am doing — this is really hard; I’m afraid I’m not good at it” my friend said as she looked up at me from her bed. Just two weeks earlier, a fall in an airport led to a visit to the Emergency Room, a diagnosis with end-stage cancer, and quickly to this room in a nursing facility. Death was not a new experience for her. Decades as a minister had given her the opportunity to contemplate death, to preach about death, and to sit exactly where I was sitting: at the bedside of a dying friend. Yes, she knew intellectually just how challenging the journey of a terminal illness can be; she had witnessed it countless times. But what was new to her was the interior experience of that journey and its at times seemingly unbearable challenges. So when she shared with me about those difficulties (with only those two phrases: “this is really hard” and “I’m not good at it”), it was almost with a bit of surprise. She was neither dramatizing those challenges (as many of our cultural constructs of death can do) nor attempting to diminish them with spiritual platitudes (as many of our cultural constructs of death can do). But she was reflecting two dominant beliefs in our culture ~ that dying should be easy and that we should be good at it.

“This thing I am doing — this is really hard; I’m afraid I’m not good at it” my friend said as she looked up at me from her bed. Just two weeks earlier, a fall in an airport led to a visit to the Emergency Room, a diagnosis with end-stage cancer, and quickly to this room in a nursing facility. Death was not a new experience for her. Decades as a minister had given her the opportunity to contemplate death, to preach about death, and to sit exactly where I was sitting: at the bedside of a dying friend. Yes, she knew intellectually just how challenging the journey of a terminal illness can be; she had witnessed it countless times. But what was new to her was the interior experience of that journey and its at times seemingly unbearable challenges. So when she shared with me about those difficulties (with only those two phrases: “this is really hard” and “I’m not good at it”), it was almost with a bit of surprise. She was neither dramatizing those challenges (as many of our cultural constructs of death can do) nor attempting to diminish them with spiritual platitudes (as many of our cultural constructs of death can do). But she was reflecting two dominant beliefs in our culture ~ that dying should be easy and that we should be good at it.

Here’s what is true about death: it is hard. It is hard on a multitude of levels: physical, emotional, spiritual, relational, and egoic. None of this is new; dying has always been really hard. However, it seems to me that dying in our culture may have its own particular challenges that have little to do with dying at all and everything to do with our culture.

We are given beautiful visions of death through many media sources. Movies, novels, and television shows present us with peaceful patients gently floating away from this realm into whatever happens next, having made peace with the struggles of their lifetime, after forgiving all those who have hurt them and being forgiven by those they have harmed. And these types of deaths do happen . . . but not always. And, even when they do, they are still very challenging to navigate. No one endures a terminal illness without pain and difficulty. However, this is not what so many people want to accept. We continue to tell stories about “good” deaths, serene people who transform during their dying into peaceful, accepting, loving models of humanity. Palliative care physician BJ Miller tells us

“Most people aren’t having these transformative deathbed moments. And if you hold that out as a goal, they’re just going to feel like they’re failing.”

During my first death walk, I experienced a great deal of spaciousness and opening, what I believe many people are referencing when they use the word “acceptance” in association with death and loss. After a miracle surgery and recovery period, I began to reflect on my journey. And I honestly felt that I had learned how to do this dying process. I had mastered this death thing.

Eighteen months later, I was shown how wrong I was. Immediately after the birth of my second child, I went back into heart failure. The months I spent on that death journey were very different than those of my first dying experience. This time, my physical pain (which was also present during my first death walk) was woven together with fear (which I had encountered only sporadically and briefly the first time), anger (which had not arisen in relationship to my dying before), and guilt (I questioned why I had chosen to bring a child into a world where she would soon be motherless). And each of those emotions was exacerbated by my self-judgment. I kept thinking, “You know how to do this; why is it so different this time?” I wondered what had happened to the skills I gained — my mastery of death — during my first experience with dying.

It now baffles me that in our culture of mastery many of us have come to truly believe that dying can be mastered – indeed, that it should be mastered. During my years of accompanying others as they die I have witnessed much of the full spectrum that death has to offer us; but I have never witnessed mastery.

It now baffles me that in our culture of mastery many of us have come to truly believe that dying can be mastered – indeed, that it should be mastered. During my years of accompanying others as they die I have witnessed much of the full spectrum that death has to offer us; but I have never witnessed mastery.

Any time spent reading contemporary literature about death and dying will quickly lead to phrases like “good death” and “dying well”. Such phrases (along with “death with dignity” and many more) are applied frequently in modern thanatological discussions. These phrases can and do lead to significant contemplations, both individually as we face our own dying and collectively as we attempt to create systems of support for the dying. Yet inherent in these types of phrases is a judgment system; to say that someone died a “good death” implies that we know what death should be like. It also is predicated on the belief that our view of a death from the outside reflects the inner experience of the one dying. We essentially judge one another’s experiences and our own, deciding what is desirable in death and what is not – when very little of the dying process is under our control. Is this what we want to do to ourselves? To view our final acts, our final days in this lifetime through the lens of mastery? It seems to me in our culture we do way too much of that judging and comparing throughout our lifetimes; our dying needs to be a place where mastery is not even considered.

As Frank Ostaseski, a worker in end-of-life care for decades, notes:

In our culture, we like to nurture a story of what it means to have a ‘good death.’ We treasure the romantic hope that when people pass away, everything will be tied up neatly. All problems will have been resolved, and they will be utterly at peace.

But this fantasy is rarely the reality. The ‘good death’ is a myth. Dying is messy. People who are dying often leave skid marks, dragging their heels as they go. (Ostaseski, The Five Invitations)

As a culture, we do hold certain visions of certain types of death as goals, and most of us end up feeling like we are failing. We worry that we are somehow getting it wrong, when in truth there is no way to “do” death incorrectly. It always happens; people always succeed at dying.

So how can we approach our dying, then? Should we just give up any attempts to do it mindfully, to be involved somehow in the flow of this most natural of processes?

Perhaps the information that has helped me navigate my dying – not my good death or my dying well, but my own, unique dying — comes not from the field of end-of-life care at all. Rather, I stumbled upon this work through parenting teenagers in this culture of mastery in which we live.

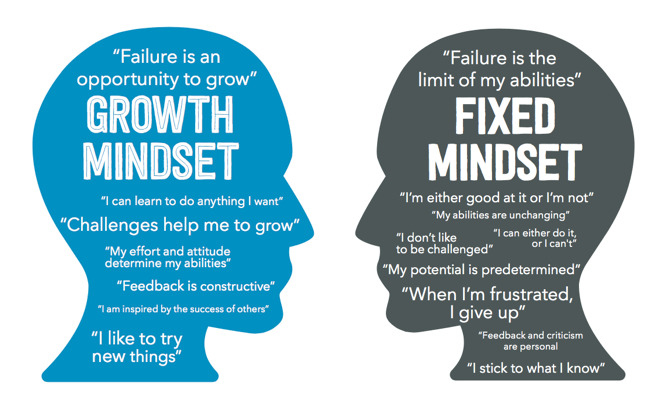

Carol Dweck, a social psychologist and professor, has spent years studying the mindset psychological trait. Very simply, a Fixed Mindset is one that views ability as fixed, predetermined, and innate; a Growth Mindset, on the other hand, believes that persistence and curiosity lead to greater learning and growth. Many, many experiments have been conducted over the past few decades, and what they each indicate is that children with Fixed Mindsets will avoid attempting challenges at which they feel uncomfortable or unknowledgeable; indeed, they will dodge all arenas where they fear they may fail. Growth Mindset children, on the other hand, place value in trying, in experimenting, in learning new things, regardless of their ability to master them. The latter group experiences less stress, and often ultimately more “success” – because they equate success with trying and growing rather than with mastery. People with Fixed Mindsets dread failure, because they view it as indicative of something they inherently lack. On the other hand, Growth Mindset folks don’t view failure as failure at all; rather, it is evidence that they attempted to learn something or grow in some way.

Some children with Fixed Mindsets, usually those who are early on labeled as “Gifted and Talented”, avoided participating fully in parts of these experiments they were told were really challenging and were beyond their ability level. The Growth Mindset kiddos, though, dove right in with those activities, believing that they would learn from them.

The wonderful thing is that we can create Growth Mindsets – not only in our children, but in ourselves as well. And this is what I advocate with death and dying. None of us has any greater innate ability to die than anyone else; none of us has experience dying until we begin to die. And this is not an arena we can avoid, no matter how much we fear failing at it.

But it is an area for experimenting, for learning new things, for curiosity, and for growth. It is a vast, wild landscape where we can become more intimate with ourselves, with those we love, and with life itself. So can we develop Growth Mindsets about our dying? Can we dive right in, knowing that there will be many failures along the way but that we will learn with each one?

One of my hospice colleagues has a beautiful refrain she says to our patients as she sits at their bedside during their final hours. Stroking their hands or gently touching their faces, she repeats over and over, “You are doing a great job.” The first time I witnessed this, I bristled a bit, having long ago confirmed for myself that there are no “good deaths.” But through the years I watched and listened; and what I noticed was this: she says this, no matter what is occurring. To the person in terminal agitation, grasping at bed sheets and clothes, she says the same thing. To the person who has lain there peacefully for days, never opening eyes or uttering a sound, she says the same thing. To the person writhing in physical pain or in emotional agony, she says the same thing. Always: “You are doing a great job.” And I know deep in my heart that each time she says these words she speaks the truth.

I chuckle sometimes as I think about her phrase. It reminds me of all the “participation trophies” handed out at soccer banquets and speech competitions, kindergarten field days and high school art shows. Although many people criticize this practice, arguing that it robs children of their natural desire to compete and excel, I think this is exactly what we need with death and dying. No one gets a gold medal, a blue ribbon. We all have messy bits; we all have beautiful times. And we all arrive at the finish line.

After watching my friend’s ritual for years, I realized that I do the same thing as my colleague does, albeit without words. For me, the words “great job” can activate mental activity that feels like judgment, comparison, and competition — each of the hallmarks of our culture of mastery. So I choose instead to remain quiet but to truly believe that whatever this person is doing as he or she lies dying, it is a great thing. Because it is.

Through my three separate death journeys, I have experienced many times of peace. I also have experienced seemingly unbearable pain. I have been in states of consciousness that resemble Western concepts of Heaven; but I have also visited states of consciousness that are best associated with Western constructs of Hell. I have spent years of my lifetime navigating the terrain of dying, both my own dying and that of those I serve.

And I have learned that dying is nothing I can master, but also that it is nothing that I need to master. What I know without a doubt is that death masters us in the end. Death is the master; we are the students. And the lesson ends only with our final breath.

2 comments to “Becoming Experts at Dying: Death in a Culture of Mastery”

You can leave a reply or Trackback this post.

Gary - August 14, 2017 at 12:16 pm

Thanks for these good thoughts

Amy Agape - August 14, 2017 at 8:07 pm

Thanks for reading and connecting, Gary!