Dualities in Dying

As I began to gather resources to help me learn how to die, I quickly became aware of the predominant language used to discuss protracted deaths; people talked and wrote about “peaceful” deaths and “good” deaths and “dying well”. And none of these phrases felt good to me; indeed, none felt life giving. Where there is a good, there is a bad; when something can be done well, it can also be done poorly; peaceful exists in contrast to violent. More boundaries. More division. More duality.

I immediately knew that there were right ways to do this dying and wrong ways, and I instantly began to feel the pressure of doing a good job. During a time when I had so little control over almost all aspects of my life (and certainly over whether it continued or not), I experienced judgment from myself, from others, and from my culture about how I was doing with “being dying”.

I became pregnant with my second child nine months after my first death journey. The risks associated with this pregnancy were incredibly high both to the child and to myself. All my hometown doctors advised against it, as did most of my family members and friends. I grappled greatly with the decision of whether to attempt to carry this child to term, eventually deciding to trust the life that was moving through me.

Moments after my baby girl arrived, with her dark head of hair and her first fierce wails, I felt my heart become severely compromised. It was not able to process the fluids coursing throughout my body. I watched my feet grow to twice their usual size in the span of a few hours. I began to cough and wheeze and fight for air. I knew I was back in the realm of dying, where I had lived just eighteen months before.

I was also in the realm of brand new existence. Holding my daughter, I marveled at the cycle of life – this newborn in my arms was just learning to breathe and take in sustenance as I was attempting to remind my lungs how to breathe, my heart how to regulate itself. I could be present physically for my daughter; I held her and nursed her, just as I had done with her brother. But something was very different. In the middle of the night, I found us both on the couch in the dark, her nursing and me coughing. And I often felt unable to be there fully with her. After learning how to be present to my own dying process just eighteen months earlier, I now encountered emotional and mental anguish that often prevented me from remaining conscious and aware during this experience. Unlike before, when I had spent months traveling to beautiful realms and feeling peaceful during my first encounter with death, I discovered that this time I was often in psychological states very far from those blissful ones.

Part of what I found so challenging about this death is that I thought I had learned all there was to know about the dying process; I thought I knew how to do death well or at least how I did death well. I knew all about “good” deaths and “peaceful” deaths. I constantly compared this second encounter with death to the previous experience and wondered what was different this time. Some of those musings led me to deep levels of self-inquiry, others to places of rigorous examination of our cultural standards of support for the dying. Each of them presented me with a different lens in the increasingly complex kaleidoscope of death.

I frequently found that I blamed myself for how I had handled this reunion with death, finding my performance this time to be greatly flawed. “What am I doing incorrectly to cause all this suffering?” I wondered. Often unable to visit the peaceful states that had become commonplace during my first dying process, I judged myself harshly in a manner that seems reminiscent of some frightening descriptions of The Last Judgment. And I repeatedly condemned myself to the realms of Hell.

Eventually, I rejected each of these terms of judgment related to dying; I threw away “good” and “well” and “wise” and “peaceful” in favor of a phrase that much more closely reflects my experience of what is possible and what is true during our dying: Conscious Death and Dying.

Conscious Death and Dying

Conscious Death is the process of utilizing our dying as an entrance point into deeper presence and awareness. Unlike a “good death” or “death with dignity,” conscious death must be defined by each individual dying based on his or her capacity and desire for presence and awareness. It cannot be gauged from the exterior; only experienced – moment by moment – from the interior. Rather than avoiding any aspect of the dying process, someone wishing to die consciously will work to become more present to each moment – as she is able. Some days when I am dying, I feel the need for large amounts of pain medications, others I do not. At some points during my dying, I can be present to and with my experience, while in some moments I need to work to escape that experience in tiny doses. When I work with consciously dying, I try to become aware of my experience in every single moment and honor that in whatever ways I am able – without judgment or any preconceived notion of how I “should” be behaving, feeling, and living/dying.

What I know is that when we are on our deathbeds it may be too late to begin to wake up to dying. It may be too late, because usually during terminal illness our energy decreases, our bodies experience pain, and our minds become less alert. If we wait until our deathbeds, we also miss the opportunity to use Conscious Dying throughout our lives – that is, to allow each of life’s “little deaths” to bring us to more awareness about the present moment, to move us to live more fully.

Non-Dual Consciousness

These dichotomies — good death vs bad death, well vs ill, peaceful vs violent, living vs dying – are each products of a Dualistic Consciousness. As James Finley and others describe it, Dualistic Consciousness is the consciousness of “otherness”; every object, every experience is defined by what it is not. Dualistic consciousness is factual; it is objective. And it is entirely necessary for each of us to be able to access this kind of consciousness. It views reality as an object, and objects can be measured and manipulated. My healthcare would not be possible without dualistic consciousness. It is imperative that my physicians see my heart as an object, its functions as measurable and even able to be manipulated. I must be able to gauge my exercise capacity, my shortness of breath, and my oxygen levels in order to track many aspects of my wellness so that they can be treated.

Without this way of thinking and approaching the world, without Dualistic Consciousness, I would not be alive.

The tricky thing, though, is that many of us who are dying frequently do not exist in Dualistic Consciousness; rather, we may find ourselves immersed in Non-Dualistic Consciousness, often without any effort. The phrase “while I was dying” conveys just a bit of that non-dualism. “To be” as a living organism indicates life itself, while “dying” refers to the cessation of that life. When we encounter protracted deaths, we can become acutely aware of both the living and the dying and the lack of separation between the two. Indeed, many people will first make this discovery on their deathbeds. We may only become aware of this lack of duality for the first time as we are dying.

That is unfortunate, because becoming aware of the non-duality of living and dying can change our lives entirely. When we pay attention to not only what is alive around us but also to what is dying, when we practice consciously dying, something profound happens. We realize that to be alive is, in many ways, to be dying. The two are intimately intertwined. Allowing ourselves to awaken to what is dying and living right now is fundamental to being most alive. And in my experience, Contemplative Practices provide precious support in this process.

Contemplative Practice

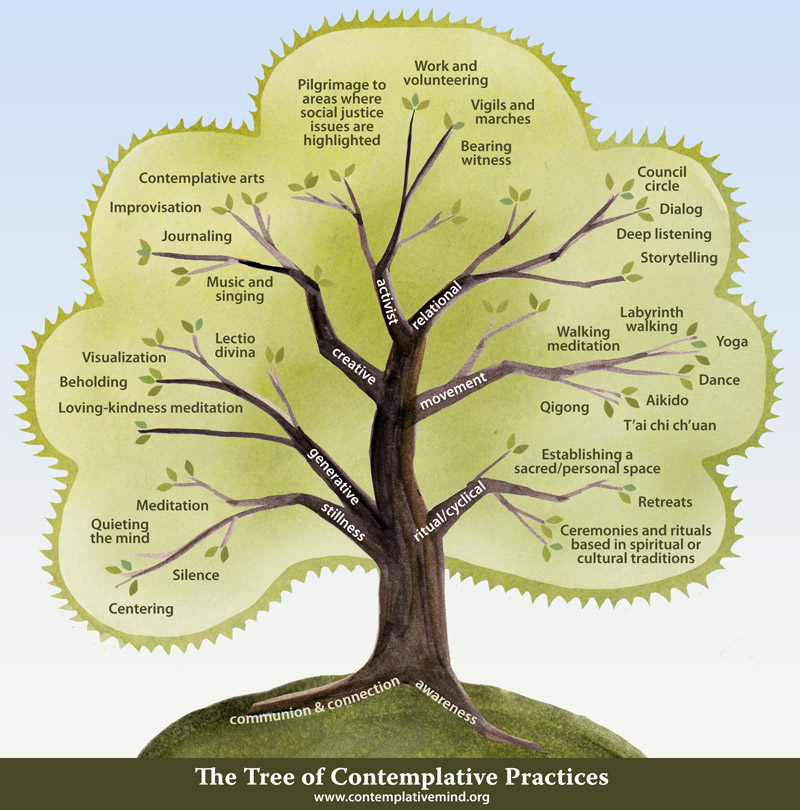

Contemplative Practice can take a multitude of forms, which are practiced throughout the globe by people of all different faith traditions and even those without connection to a specific faith tradition. Quiet prayer, with or without words, can be contemplative; creating artwork can be contemplative; even running can be contemplative. Indeed the term “Contemplative Practice” has more to do with the manner in which a practice is conducted than it does with the form of that practice itself.

The Center for Contemplative Mind in Society describes Contemplative Practices as those that:

“cultivate a critical, first-person focus, sometimes with direct experience as the object, while at other times concentrating on complex ideas or situations. Incorporated into daily life, they act as a reminder to connect to what we find most meaningful.”

“Contemplative practices are practical, radical, and transformative, developing capacities for deep concentration and quieting the mind in the midst of the action and distraction that fills everyday life. This state of calm centeredness is an aid to exploration of meaning, purpose and values. Contemplative practices can help develop greater empathy and communication skills, improve focus and attention, reduce stress and enhance creativity, supporting a loving and compassionate approach to life.”

and provides this Tree of Contemplative Practice to illustrate the wide variety of ways contemplation may be observed:

To use any of these practices to turn our attention to first-person focus and to connect with what is meaningful can be profound support on our deathbeds – and in every other situation we encounter that precedes it.

Practicing for Death

In general, I have found that the practices and tools presented to persons wishing to create conscious dying experiences can be organized into four major categories: Illuminative, Purgative, Unitive, and Kenotic. In fact, what I have discovered is that each of these categories signifies a distinct movement of transformation that occurs during the dying process. The terminology I am using originates in the Western Christian tradition; however these movements it encompasses are not tradition-specific. Rather, they are the changes every human experiences throughout living and dying.

Why then should we practice with them?

As I found with my first death journey, most of us are not skilled at allowing these changes to happen. These natural transformations that occur throughout our lifetimes may be movements we try to avoid and even deny. And when we spend a lifetime avoiding such transformations, those that happen as we are dying can be much more challenging to meet.

So instead we may choose to practice dying. Keep following along here to learn more, and if you are able please join us at Naropa University’s Conference on Compassionate Approaches to Aging and Dying:

Practicing for our death can look like participating in ancient rituals and ceremonies. It may also happen through sitting on our cushion in meditation, moving our bodies in yoga class, and becoming acutely aware of the plants that are dying in our garden. There is a wealth of guidance and support for our practicing for death. Some of it originates in the traditions of ancestors long gone, and some of it streams toward us from the vast amounts of material found in end of life care manuals and death data from medical, psychological, sociological, and religious realms today.

Throughout this blog series, we will explore several types of practices for dying. Death is not merely one final happening in a lifetime; it is not the finish line that we are forced toward as we take our final breaths. Rather, all deaths are integral to our life – both our final, physical deaths and all the smaller deaths we experience on the way to that last event. And we can use those smaller deaths both to help ourselves prepare for our physical dying and to help us live each of our days more abundantly. Without allowing ourselves repeatedly to die throughout our lives, we likely will find ourselves struggling against death as our physical bodies decline. We will resist the natural flow of life in our attempt to keep living, so that ultimately our obsession with living robs us of our ability to live fully.