It was a cold January day; I was sitting at my computer working on a particularly challenging dissertation chapter, one that studied the state of death in contemporary Western culture – how we talk about death, how we support the dying, types of education we create about death, dominant approaches to death in our world today. A friend sent me a text message informing me that musician David Bowie had died. One moment, I was witnessing and commenting on that world – the collective construct of death we together have created and continue to create – and the next I felt pulled into that world. I discussed Bowie’s death with many people; I listened to the music he had released two days before he died and watched his last video, Lazarus, repeatedly, allowing the imagery to pull me further into our culture’s discussion about death and dying

It was a cold January day; I was sitting at my computer working on a particularly challenging dissertation chapter, one that studied the state of death in contemporary Western culture – how we talk about death, how we support the dying, types of education we create about death, dominant approaches to death in our world today. A friend sent me a text message informing me that musician David Bowie had died. One moment, I was witnessing and commenting on that world – the collective construct of death we together have created and continue to create – and the next I felt pulled into that world. I discussed Bowie’s death with many people; I listened to the music he had released two days before he died and watched his last video, Lazarus, repeatedly, allowing the imagery to pull me further into our culture’s discussion about death and dying

(https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y-JqH1M4Ya8).

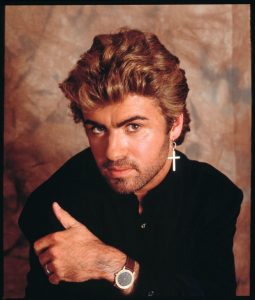

And 2016 ended with similar collective conversations about death. The holiday news of the deaths of George Michael, Carrie Fisher, and Debbie Reynolds had people considering causes of death as well as the not entirely unusual phenomenon of family members dying one right after another; and there were a multitude of lamentations. For many people, 2016 was a year filled with the deaths of people they admired and respected but had never met. I do not know the average number of celebrity deaths each year, nor do I know what even constitutes a “celebrity” in this case.

And 2016 ended with similar collective conversations about death. The holiday news of the deaths of George Michael, Carrie Fisher, and Debbie Reynolds had people considering causes of death as well as the not entirely unusual phenomenon of family members dying one right after another; and there were a multitude of lamentations. For many people, 2016 was a year filled with the deaths of people they admired and respected but had never met. I do not know the average number of celebrity deaths each year, nor do I know what even constitutes a “celebrity” in this case.

It does appear as though many people believed there to be more such deaths in 2016 than they had experienced before. Perhaps the re were just more deaths that touched them.

re were just more deaths that touched them.

(for a list of celebrity deaths in 2016, see http://www.syracuse.com/celebrity-news/index.ssf/2016/01/celebrity_deaths_in_2016_famous_photos.html).

I once listened to a very wise woman speaking about the death of someone close to her. A group of us had gathered together under the guidance of Mirabai Starr to spend a week exploring through writing, sharing, and spiritual practice the depths of loss (Starr’s ability to create safe, sacred spaces through which people can explore grief and transition is remarkable; if this is something that draws you, please consider attending one of her Writing Your Story of Loss and Transformation workshops: http://mirabaistarr.com/writing-workshops/ ). And this wise woman said, “This being human is absolutely unbearable at times”. Everyone in the circle agreed. Some had lost children, others spouses and partners. We all knew deep in our hearts the unbearability of having death steal from us someone or something we love. I have had the privilege of providing grief support for bereaved persons for decades; and this November and December I sat with a circle of dedicated people, each of whom had lost someone very close to them during the past year. Together, they were supporting one another in navigating the very treacherous terrain of the first holiday season after the death of a loved one. Yes, this being a human can be absolutely unbearable.

The poet David Whyte describes a bit of his experience of this unbearability; his friend and fellow poet John O’Donohue died in 2008, and :

. . . when he went, it was like the other half of me disappeared. And we have this physical experience in loss of falling toward something. It’s like falling in love except it’s falling into grief.

And you’re falling towards the foundation that they held for you in your life that you didn’t realize they were holding. And you fall and fall and fall and you don’t find it for the longest time. And so the shock of the loss to begin with, and the hermetic sealing off, is necessary in grief. http://www.onbeing.org/program/david-whyte-the-conversational-nature-of-reality/transcript/8581

When we lose someone dear to us, that experience of falling, of feeling like half of us has disappeared, is real – tactile and intense and at times unbearable. And if we live long enough and open ourselves to love, each of us will experience just such loss.

But what about mourning those we don’t know? It is not as though a part of us is now gone; is it? Can that even be called “mourning” if the person who has died is not someone in our personal lives? And, if so, what are we really mourning? My daily life will not be changed in any major way by the absence of any of the celebrities who died this year. Unlike those who were close to them, I will not wake up, roll over, and reach for the beloved who no longer shares my bed. I will not pass the spot where we used to meet for lunch and feel my heart lurch. I will not pick up my phone to call someone special before realizing that no one will answer that number, ever.

So why does it still feel to many people like they have lost someone – or perhaps something – when a celebrity dies? What are we really grieving when we mourn the loss of a celebrity? Have we perhaps lost a part of ourselves? These deaths are not unbearable, as are those of people close to us. They do not change our lives, rearrange our psyches, or leave us wondering how the planet could possibly continue turning.

And yet there is grief of some sort. What is that grief?

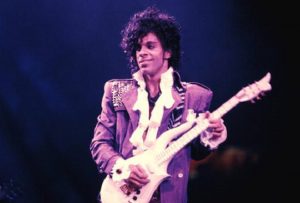

It seems to me that we are mourning something about ourselves when we grieve the death of a celebrity; in some way, it seems as if we have lost part of ourselves. We are grieving the passing of a time in our lives, and in many instances that time has passed long ago. The music of David Bowie, Prince, and George Michael formed the soundtrack of my growing-up years. Similarly, for many people, Carrie Fisher’s Princess Leia or Debbie Reynold’s Tammy became icons of their own youth.

Somehow, when these artists die, we are instantly transported to those periods of our lives represented by their creations, whether they occurred yesterday or decades ago. We glimpse ourselves through the lens of their passing, and that can lead to feelings of loss. For me, the deaths of those musicians prompted memories I may not have accessed for years. . . yet there those memories were, rich and vibrant and very tender. Listening to that music again felt like visiting teenage Amy. And I felt a sense of grief for parts of her that may not seem present anymore. I will never again sit on a bus with my friends, riding home after cheerleading practice and listening to Raspberry Beret, Careless Whispers, or China Doll on my Walkman, whispering about how cute Prince, George Michael, and David Bowie are. So it would seem that that me, the one in the cheerleading uniform with the Walkman, is gone. And this is what I believe we grieve with the death of celebrities – the parts of us we feel are gone forever.

But as with all deaths, what deep exploration of loss may lead us to is an appreciation that the past is interwoven with the present and even the future in subtle but significant ways.

David Whyte continues his discussion of loss:

And so there’s this really astonishing melding that occurs, which is a kind of dreamtime, which human beings start to move into in their maturity, actually, where what is past, what is present, and what’s about to occur are not so clearly marked out. One of the things the Irish say is that “the thing about the past is it’s not the past.” It’s right here in this room, in this conversation. (http://www.onbeing.org/program/david-whyte-the-conversational-nature-of-reality/transcript/8581)

Maybe, even though these particular celebrities have died, and I feel like their deaths somehow indicate the passing of something in me – youth or innocence, perhaps — maybe the Irish are right. Maybe me moving into my maturity catalyzes a deep realization that the past is not the past. Maybe all of it is right here in this room, in this conversation.